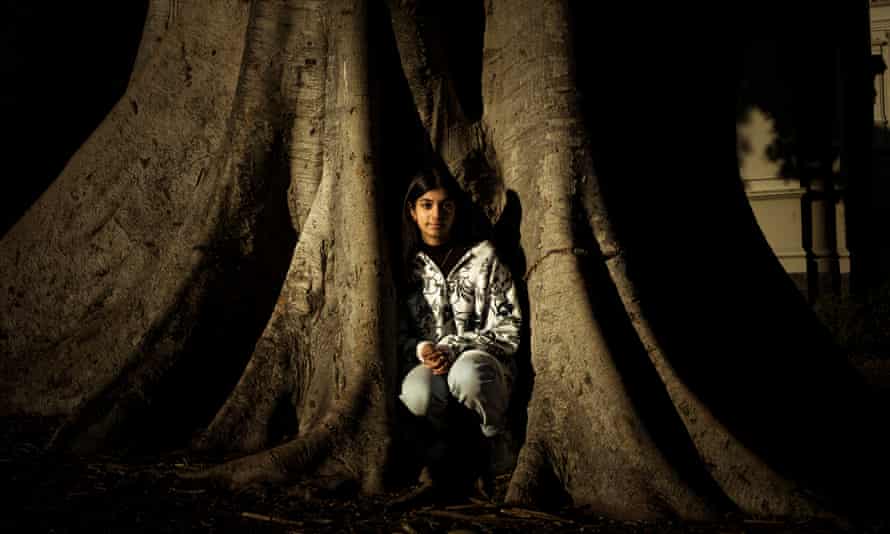

At about 9.30am on Thursday morning, 17-year-old Melbourne school student Anjali Sharma was walking her two-year-old kelpie-cross dog Maya down to the creek when the notifications started buzzing on her phone.

“I was getting updates from the lawyers in the court,” says Sharma, who as we speak is about to take another call from a journalist at the Times of India.

At the federal court in Melbourne, Justice Mordecai Bromberg was handing over his final orders in a case taken by Sharma and seven other school children – aided in court by Sister Brigid Arthur, a nun some 70 years their senior.

With a short reading to the court, the judge formalised into law that Australia’s environment minister had a duty of care to “avoid causing personal injury or death” not just to Sharma and her friends – but all Australians under 18 – “arising from emissions of carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere”.

The Australian government took just 24 hours to announce it would appeal.

In May, Bromberg had rejected the children’s bid to block the expansion of the Vickery coalmining project (back then, Sharma was livestreaming the court on her laptop while in an economics class at Huntingtower school).

But he agreed with arguments from their legal team that when it came to making a decision on the mine, Australia’s environment minister had a duty of care to protect them from the ravages of the climate crisis.

“As Australian adults know their country, Australia will be lost and the World as we know it gone as well,” he wrote. “Trauma will be far more common and good health harder to hold and maintain.

“None of this will be the fault of nature itself. It will largely be inflicted by the inaction of this generation of adults, in what might fairly be described as the greatest inter-generational injustice ever inflicted by one generation of humans upon the next.”

The judge’s words were affirmation for the children.

What is now known as the “Sharma case” is being closely followed by climate litigators around the world, who say it has done something that none of the 1,800 or so cases around the world since 1986 have managed.

Kate Higham co-ordinates Climate Laws of the World – a platform that tracks climate cases around the world at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

She says the Sharma case is the “first in which a common law court has recognised the existence of a government duty of care to avoid climate harms that is based in the law of negligence.”

Only 10 cases have tried the approach, and only one so far has been successful in common law.

Failing arguments

“It’s hard to come to terms with the scale of all this,” says Sharma, “knowing people globally have their eyes on this too.”

When governments or companies have been challenged in court about the impacts of fossil fuels on the climate, their defences have fallen broadly into two common categories.

Either a project is too small to make a difference, or stopping it won’t make a difference because the energy market will just fill the gap with fossil fuels from somewhere else.

Elaine Johnson, director of legal strategy at the Environmental Defenders Office in Sydney, says the Sharma case shows that these two defences are now being dismissed by judges.

“We have now reached a point in time with respect to the global carbon budget, where these arguments no longer hold water. One more mine does make a difference and it adds cumulatively to emissions that are already in the atmosphere.”

In the Sharma case, lawyers for Australia’s environment minister put what Prof Jacqueline Peel describes as the “drop in the ocean” defence to the court.

Burning an extra 33 million tonnes of coal from the mine, the government’s lawyers argued, was the difference between 2C of warming and 2.00005C of warming. At such a small scale, there was no evidence before the court on how that would relate to the risk faced by the young people. That argument failed.

“That does not mean the mine has a trivial impact,” says Peel, a climate litigation expert at the University of Melbourne. “Any emissions could get us over a tipping point [in the climate] into more dangerous scenarios.”

Johnson was the lead lawyer in a breakthrough case in 2019, where plans for the Rocky Hill coalmine in New South Wales were stopped by a judge partly because of its potential climate impact.

In that case the company, Gloucester Resources, made what Peel calls the “market substitution” defence – also known as the drug dealers defence.

Gloucester Resources argued if their mine was blocked, the global demand for coal would mean it would simply be mined elsewhere. “The market substitution argument is also flawed,” wrote Justice Brian Preston in his judgement.

“Developed countries such as Australia have a responsibility, including under the climate change convention, the Kyoto protocol and the Paris agreement, to take the lead in taking mitigation measures to reduce [greenhouse gas] emissions,” Preston wrote.

“We said [the Rocky Hill mine] was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” says Johnson. “It’s the wrong time because emissions need to be dramatically reduced.”

‘Australian government is offloading its responsibility’

The LSE’s climate litigation database shows since 1986, there have been more than 1,800 cases in courts around the world. Outside the United States, where there have been 1,398 cases, there have been more cases in Australia (115) than anywhere else.

César Rodríguez-Garavito, professor of clinical law and director of the Climate Litigation Accelerator at New York University School of Law, says one reason for Australia’s outsized representation is down to persistent government failings and its position as a major fossil fuel exporter.

Analysis has suggested emissions from burning Australian coal overseas is almost double the nation’s domestic footprint.

“Effectively, the Australian government is offloading its responsibility for climate change not only to young people but also to the rest of the world,” says Rodríguez-Garavito.

“In the face of the government’s inaction and breach of its duty of care to young people, litigants have had to resort to courts to enforce that duty and nudge the government into complying with international law and scientific recommendations.”

What has changed?

The rate that climate cases are coming before the courts has surged since the 2015 Paris agreement. Before the agreement, there had been about 800 cases. Since the agreement, there have been 1,000.

“Litigation and international agreements [like the UN Paris deal] are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they are complementary and are mutually reinforcing,” says Rodríguez-Garavito.

In essence, he says climate court cases legally enforce the scientific consensus on climate change and the international forums like the UN’s Paris agreement.

Like in the Sharma case, Higham says cases around the world are increasingly representing children.

“They are interesting because of the ways in which they challenge our understanding of government obligations to citizens over longer time horizons,” she said.

In Germany last year, a youth group argued in a constitutional court their government’s greenhouse gas reduction targets were too low and violated their humans rights.

The group won, forcing the government to adjust their targets to make greater greenhouse gas reductions sooner – meaning there was less burden on younger people to make cuts.

Johnson says the ultimate goal for climate legislation for Australia is to force the government to legislate targets “consistent with the science”.

“We have seen in the courts that the science is cutting through – they’re recognising it’s the science that matters and that’s what tells us about the level of risk that exists for children and communities.”

Johnson’s EDO has three climate cases coming up before courts in August this year and another scheduled for February next year.

Now the eight Australian schoolchildren will have to wait for a date for the government’s appeal, which could come before the end of the year.

Even before the case, Sharma says she was hoping for a career in environmental law after finishing her studies.

“My mum says this is like the most intense work experience I’ll ever have.”

Average Rating