A few summers ago when a range of policymakers, business people, academics, labour leaders and charity workers gathered at the Vatican to discuss the future of the market system, Pope Francis surprised us by joining the lunch and sharing a parable. He observed that:

Our meal will be accompanied by wine. Now, wine is many things. It has a bouquet, colour and richness of taste that all complement the food. It has alcohol that can enliven the mind. Wine enriches all our senses.

At the end of our feast, we will have grappa. Grappa is one thing: alcohol. Grappa is wine distilled.

He continued:

Humanity is many things – passionate, curious, rational, altruistic, creative, self-interested. But the market is one thing: self-interest. The market is humanity distilled.

And then he challenged us:

Your job is to turn the grappa back into wine, to turn the market back into humanity. This isn’t theology. This is reality. This is the truth.

In my experience, the upheaval the world has been experiencing demonstrates that it is vital to rebalance the essential dynamism of capitalism with our broader social goals. This is not an abstract issue or a naive aspiration.

For over 12 years, I had the privilege and challenge of being a G7 governor, first in Canada and latterly in the UK. During this time I saw kingdoms of gold rise and fall. I led global reforms to fix the faultlines that caused the financial crisis, worked to heal the malignant culture at the heart of financial capitalism and began to address both the fundamental challenges of the fourth industrial revolution and the existential risks from climate change. I felt the collapse in public trust in elites, globalisation and technology. And I became convinced that these challenges reflect a common crisis in values and that radical changes are required to build an economy that works for all.

Whenever I could step back from what felt like daily crisis management, the same deeper issues loomed. Can the very act of valuation shape our values and constrain our choices? How do the valuations of markets affect the values of our society?

As we move from a market economy to a market society, both value and values change. Increasingly, the value of something, of some act or of someone is equated with their monetary value, a monetary value that is determined by the market. The logic of buying and selling no longer applies only to material goods, but increasingly governs the whole of life from the allocation of healthcare to education, public safety and environmental protection.

Commodification, putting a good up for sale, can corrode the value of what is being priced. As the political philosopher Michael Sandel argues, “When we decide that certain goods and services can be bought and sold, we decide, at least implicitly, that it is appropriate to treat them as commodities, as instruments of profit and use.”

Putting a price on every human activity erodes certain moral and civic goods. It is a moral question how far we should take mutually advantageous exchanges for efficiency gains. Should sex be up for sale? Should there be a market in the right to have children? Why not auction the right to opt out of military service?

There is extensive evidence that, when markets extend into human relationships and civic practices (from child-rearing to teaching), being in a market can change the character of the goods and the social practices they govern.

One of the best-known examples was documented by Richard Titmuss in his comparative study of blood-donation systems in the US and the UK, The Gift Relationship. Titmuss demonstrated that in economic and practical terms, the UK system of voluntary donations was superior to the US system, which paid for donations. He added an ethical argument that turning blood into a commodity diminished the spirit of altruism and eroded people’s sense of obligation to donate blood to support others in their community.

These observations are familiar from the civic response to Covid. None of the voluntary groups that spontaneously formed were paid for the makeshift PPE and protective masks they created and donated. A call for volunteers to help those in the NHS was met with over a million people within days. No citizen drew on a government payment to help elderly neighbours or the homeless in their communities.

This underscores the moral error of many mainstream economists, which is to treat civic and social virtues as scarce commodities, despite there being extensive evidence that public-spiritedness increases with its practice.

My experience in the private and public sectors accords with Pope Francis’s parable. Value in the market is increasingly determining the values of society. We are living Oscar Wilde’s aphorism – knowing the price of everything but the value of nothing – at incalculable costs to our society, to future generations and to our planet.

Once we recognise these dynamics, we can turn grappa back into wine, and channel the value of the market back into the service of the values of humanity.

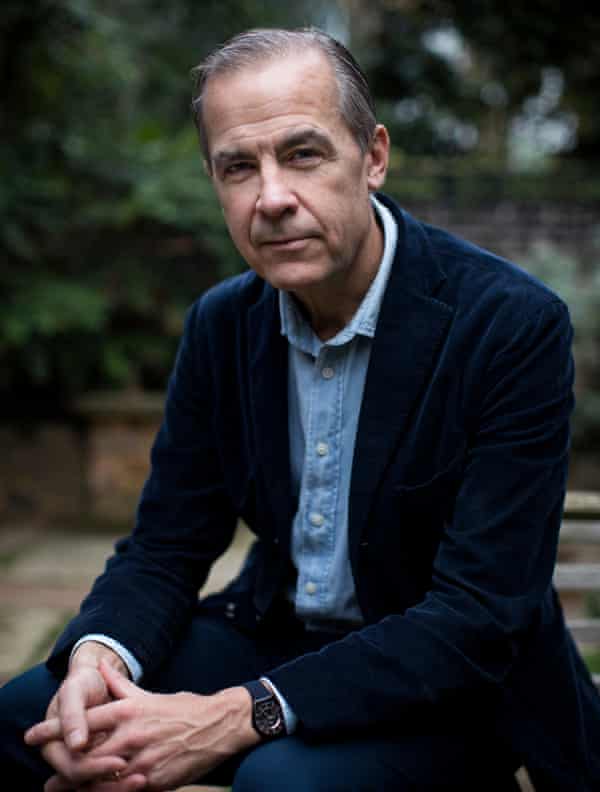

Value(s): Building A Better World For All, by Mark Carney, is published by HarperCollins, priced at £30. To order a copy for £26.10, visit guardianbookshop.com.

Mark Carney will be in conversation with Guardian political editor Heather Stewart at a Guardian Live online event on Wednesday 17 March at 7.30pm. Book tickets here

Average Rating